The Thought Process Was That Art Was Created for

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/9d/c19d6477-0e29-4c4d-9444-3d34e6d8ea12/ai-art.png)

With AI becoming incorporated into more aspects of our daily lives, from writing to driving, information technology'south only natural that artists would also offset to experiment with bogus intelligence.

In fact, Christie'due south just sold its get-go piece of AI art—a blurred face up titled "Portrait of Edmond Belamy"—for $432,500.

The piece is function of a new wave of AI art created via car learning. Paris-based artists Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel and Gauthier Vernier fed thousands of portraits into an algorithm, "didactics" information technology the aesthetics of past examples of portraiture. The algorithm then created "Portrait of Edmond Belamy."

The painting is "not the product of a man heed," Christie's noted in its preview. "It was created by artificial intelligence, an algorithm defined by [an] algebraic formula."

If bogus intelligence is used to create images, tin the final product really exist idea of equally fine art? Should at that place be a threshold of influence over the final product that an creative person needs to wield?

As the director of the Art & AI lab at Rutgers Academy, I've been wrestling with these questions – specifically, the indicate at which the artist should cede credit to the automobile.

The machines enroll in art class

Over the concluding l years, several artists accept written computer programs to generate fine art – what I call "algorithmic art." It requires the creative person to write detailed code with an actual visual outcome in mind.

Ane the earliest practitioners of this form is Harold Cohen, who wrote the plan AARON to produce drawings that followed a set of rules Cohen had created.

But the AI art that has emerged over the past couple of years incorporates machine learning technology.

Artists create algorithms not to follow a set of rules, but to "learn" a specific aesthetic by analyzing thousands of images. The algorithm so tries to generate new images in adherence to the aesthetics it has learned.

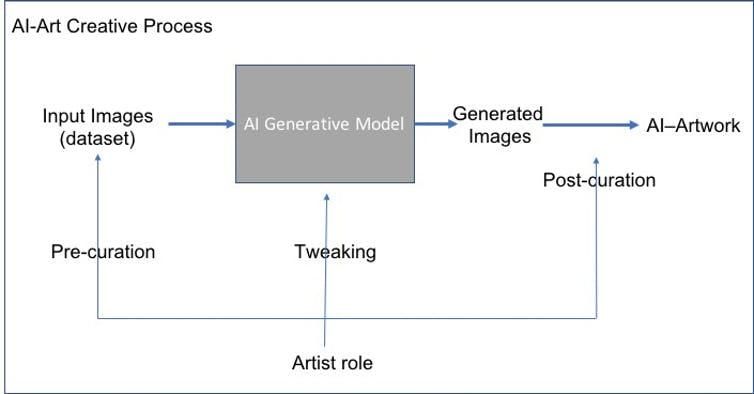

To begin, the artist chooses a drove of images to feed the algorithm, a step I call "pre-curation."

For the purpose of this instance, permit's say the artist chooses traditional portraits from the past 500 years.

Most of the AI artworks that take emerged over the past few years have used a class of algorithms called "generative adversarial networks." First introduced by computer scientist Ian Goodfellow in 2014, these algorithms are called "adversarial" because there are ii sides to them: Ane generates random images; the other has been taught, via the input, how to judge these images and deem which all-time align with the input.

So the portraits from the past 500 years are fed into a generative AI algorithm that tries to imitate these inputs. The algorithms and then come up back with a range of output images, and the creative person must sift through them and select those he or she wishes to use, a step I telephone call "post-curation."

So in that location is an element of creativity: The creative person is very involved in pre- and post-curation. The artist might also tweak the algorithm as needed to generate the desired outputs.

Serendipity or malfunction?

The generative algorithm tin produce images that surprise fifty-fifty the artist presiding over the process.

For example, a generative adversarial network being fed portraits could terminate up producing a series of deformed faces.

What should we make of this?

Psychologist Daniel E. Berlyne has studied the psychology of aesthetics for several decades. He found that novelty, surprise, complexity, ambiguity and eccentricity tend to exist the virtually powerful stimuli in works of art.

The generated portraits from the generative adversarial network – with all of the deformed faces – are certainly novel, surprising and bizarre.

They besides evoke British figurative painter Francis Bacon's famous deformed portraits, such equally "Three Studies for a Portrait of Henrietta Moraes."

But at that place's something missing in the plain-featured, machine-made faces: intent.

While it was Bacon's intent to brand his faces deformed, the plain-featured faces we see in the case of AI art aren't necessarily the goal of the artist nor the machine. What we are looking at are instances in which the machine has failed to properly imitate a human face, and has instead spit out some surprising deformities.

Yet this is exactly the sort of image that Christie's auctioned.

A class of conceptual art

Does this issue really indicate a lack of intent?

I would argue that the intent lies in the process, even if it doesn't appear in the last image.

For example, to create "The Fall of the Business firm of Usher," artist Anna Ridler took stills from a 1929 film version of the Edgar Allen Poe brusque story "The Fall of the Firm of Usher." She made ink drawings from the yet frames and fed them into a generative model, which produced a series of new images that she then arranged into a short film.

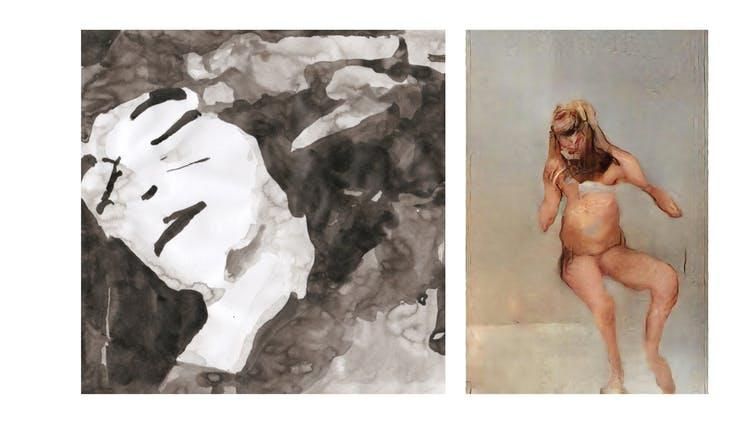

Another example is Mario Klingemann'south "The Butcher'due south Son," a nude portrait that was generated by feeding the algorithm images of stick figures and images of pornography.

I employ these two examples to show how artists can really play with these AI tools in any number of ways. While the final images might have surprised the artists, they didn't come out of nowhere: In that location was a process backside them, and at that place was certainly an element of intent.

Notwithstanding, many are skeptical of AI art. Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz has said he finds the fine art produced by AI artist boring and dull, including "The Butcher's Son."

Perhaps they're correct in some cases. In the plain-featured portraits, for example, yous could contend that the resulting images aren't all that interesting: They're really just imitations – with a twist – of pre-curated inputs.

But it's non simply nearly the terminal prototype. It'south a about the artistic process – i that involves an artist and a auto collaborating to explore new visual forms in revolutionary ways.

For this reason, I have no dubiety that this is conceptual fine art, a grade that dates back to the 1960s, in which the idea behind the work and the process is more important than the event.

As for "The Butcher's Son," one of the pieces Saltz derided as boring?

It recently won the Lumen Prize, a prize defended for art created with engineering.

As much as some critics might decry the trend, it seems that AI art is here to stay.

Editor's Notation, October 26, 2018: This story was updated with the news of Christie's selling its first slice of AI art, the "Portrait of Edmond Belamy."

This article was originally published on The Conversation. ![]()

Ahmed Elgammal, Professor of Computer Vision, Rutgers University

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/with-ai-art-process-is-more-important-than-product-180970559/

0 Response to "The Thought Process Was That Art Was Created for"

Post a Comment